Corporate profits compel Philadelphia leaders to enact a law requiring city-contracted businesses to disclose any profits from or policies on enslavement, and to create a reparations plan. Advocates say it was never enforced.

The National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America, or N’COBRA, the organization’s local chapter, requested a task force Thursday morning, before the Council’s first session of the new year.

N’COBRA also urged the city to enforce a reparations law that has been on the books since 2005 but never enforced, according to the group. That law requires city-contracted businesses and banks to disclose their historic connections to the institution of slavery and submit proposals on financial initiatives or programs designed to benefit Black people. by Layla A. Jones

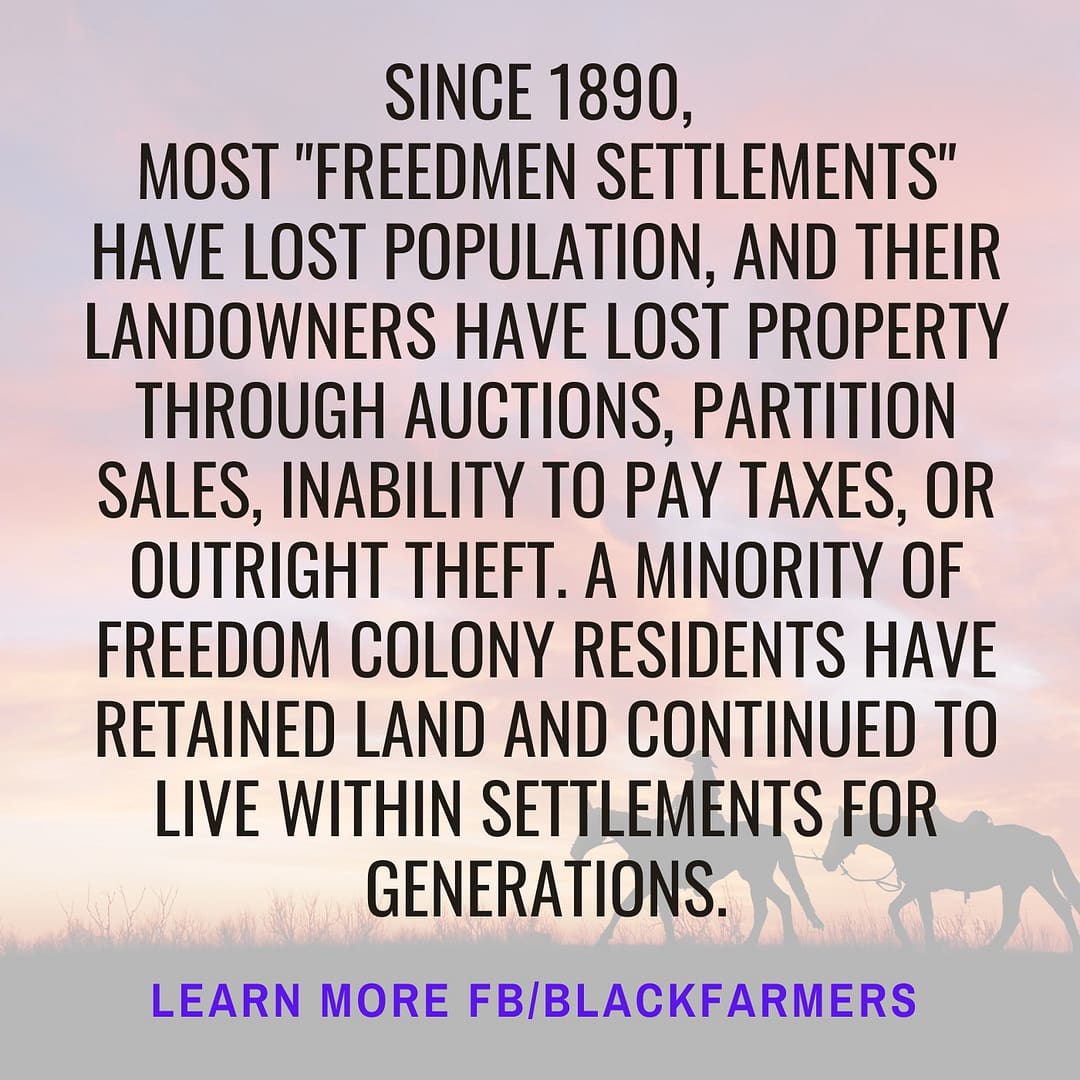

To fully understand the movement for reparations today, Daniels says Americans need to first contend with the indignities of the past. “In 1863, when newly emancipated slaves (reclassified with other non-whites as Freedmen) were denied the 40 acres and a mule the federal government had promised them,” he explains, “it ensured that they were literally left with nothing, thrown into a hostile environment with no jobs, income, resources, education or land.”

Contrast that to the federal government’s Homestead Act of 1862, a year earlier, that “allotted 160 acres of free acreage (up to $4.76 per acre) to 1.5 million Whites settling in Western states,” Daniels adds. Contrast that to the 160-320 acres of land allotments per person to Creek Freedmen as a result of the June 14th, 1866 Treaty with the Five Civilized Tribes.

Was sharecropping slavery? Local merchants usually provided food and other supplies to the sharecropper on credit. In exchange for the land and supplies, the cropper would pay the owner a share of the crop at the end of the season, typically one-half to two-thirds. The cropper used his share to pay off his debt to the merchant.

Meanwhile, the University of Florida hired a task force to provide a report on its historical ties to free labor before, during, and after the Civil War. The report details state-wide property theft, land appropriation atop wide spread injustice on-and-off campus.

At UF, scholars in Education, and the Social, Agricultural, and Biological Sciences were engaged in the American Eugenics Movement of the Jim Crow Era, and were assimilating the scholarship of social engineering, as prescribed by notable Eugenics Movement academics and policy makers including Richard T. Ely, Edward L. Thorndike, Lewis M. Terman, Paul B. Popenoe, William Z. Ripley, Edward A. Ross, Karl J. Holzinger, Frederick M. Babcock, Robert S. Woodworth, John L. Gillin, and Leta Hollingsworth. This section of the report includes a brief appraisal of some of UF’s teaching and research archives, and reveals references to the academic work of those eugenicists listed. (ead the full report)

In San Francisco, California — a city with deep “Black and Jewish descendants” — the reparations task force recommendations (similar to Black Wall Street efforts in Tulsa) go way beyond just financial compensation. In the City of Oakland (compare Oakland, Florida) economists hired by the task force are seeking guidance in five harms experienced by Black people: government taking of property, devaluation of Black-owned businesses, housing discrimination and homelessness, mass incarceration and over-policing, and health to more effectively close the racial wealth gap. Covered in the Reparations Report, “as early as 1855, state laws were established to prevent local governments from receiving extra funding when they taught a Black student. In 1863, a California law was passed that withheld state funds from schools that taught Black children. Although Black Californians were taxed to pay for the state’s public schools, the money only paid for the education of white children. In 1874, the California Supreme Court upheld school segregation in San Francisco.”

“To understand the businesses that were lost and forced to close because of eminent domain or because of redevelopment. Or even just the folks who weren’t allowed to buy property,” Davis said.

To qualify, SF residents would have to be 18 or older, have been identifying as black or African American on public documents for at least 10 years and meet two of eight additional criteria. These may include having to prove they were born in the city between 1940 and 1996, have lived in San Francisco for at least 13 years, and be someone — or the direct descendant of someone — incarcerated during the war on drugs.

The task force must determine when each harm began and ended and who should be eligible for monetary compensation in those areas. For example, the group could choose to limit cash compensation to people incarcerated between 1970 — when more people started being imprisoned for drug-related crimes — to the present. Or they could choose to compensate everyone who lived in over-policed Black neighborhoods, like Evansville, Illinois who last year voted 8–1 on Monday to approve a first-of-its-kind initiative to distribute $400,000 to eligible black households as a form of reparations over past discrimination and the lasting effects of slavery.

View the Reparations Draft Plan for San Francisco