A nationwide study of more than 1 million military discharges finds that Black veterans are significantly more likely to “bear the stigma” of a less-than-honorable discharge.

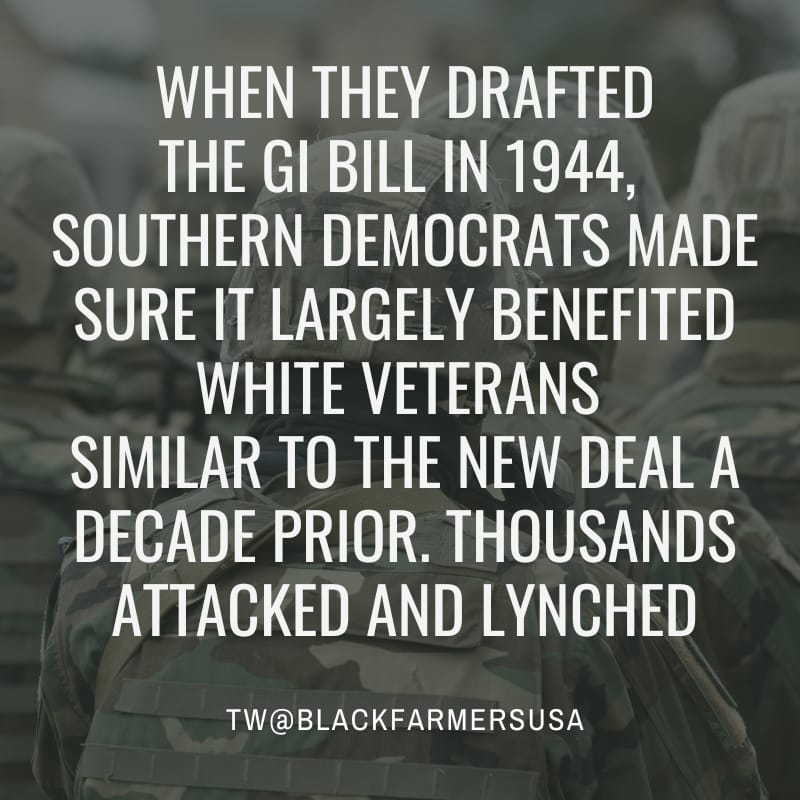

More than a stigma, those with other-than-honorable discharges “can be shut out of benefit programs ranging from housing, education, vocational training, and health care,” according to a new report, “Discretionary Injustice,” scheduled for release by the Connecticut Veterans Legal Center on Friday, Veterans Day. That follows a March report in 2022 from the Brandeis Institute for Economic and Racial Equity that says the GI Bill, often vaunted for its substantial financial assistance to those who served, actually “contributed to the racial wealth gap” and negatively impacted African Americans through its racist implementation.

The GI Bill, with free college and an easy home-loan, has been credited with helping create the modern American middle class. The federal program was administered locally, though, and segregation was still the law in 18 mostly Southern states.

“The GI bill was one of the best pieces of policy that the United States ever created. At least it was for white veterans. The fact that Black veterans weren’t able to benefit from the bill in the same way is frankly a disgrace,” says Matthew Delmont, the author of Half American, about Black soldiers in World War II.

Recently, in 2023, the disparities continue to increase for descendants of Black Veterans. Congress is considering a bill called the “VA Forever Housing Act” introduced by Whip James E. Clyburn and Massachusetts’ Rep. Seth Moulton that would grant direct education and housing benefits to descendants of World War II veterans who did not receive full GI bill benefits.

“If you were to quantify a dollar amount of how much you owe the descendants of a World War II veteran who did not receive the GI bill housing, unemployment insurance and education benefits, you would have to pay $80,000 at least,” said NBC10 Philadelphia Correspondent Lucy Bustamante. About 1 million Black Americans served during WW II — not all of them lived long enough to get the that sort of recognition, or the benefits they were promised.

● Extends access to the VA Loan Guaranty Program to the surviving spouse and certain direct descendants of Black World War II veterans who are alive at the time of the bill’s enactment;

● Extends access to the Post-911 GI Bill educational assistance benefits to the surviving spouse and certain direct descendants of Black World War II veterans alive at the time of the bill’s enactment (1944 Roosevelt Administration);

● Requires a GAO report outlining the number of individuals who received the educational and housing benefits; and

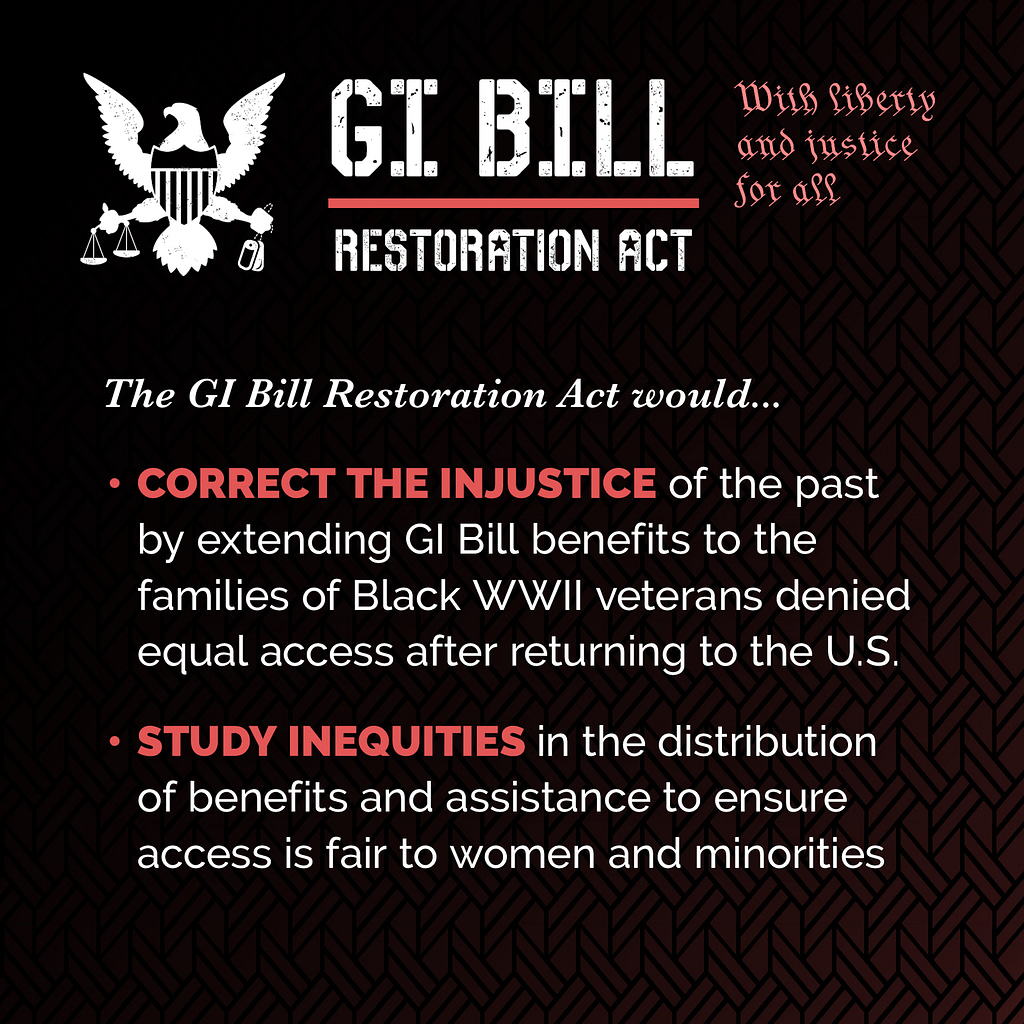

● Establishes a Blue-Ribbon Panel of independent experts to study inequities in the distribution of benefits and assistance administered to female and minority members of the Armed Forces and provide recommendations on additional assistance to repair those inequities.

Some Democratic lawmakers are trying to fix that. Their legislation, the Sgt. Isaac Woodard, Jr. and Sgt. Joseph H. Maddox GI Bill Restoration Act, would extend certain benefits to African American vets and their families, if they can prove racism affected their benefits. Woodward, a World War II veteran, was beaten and blinded in uniform by South Carolina police who dragged him from a bus in 1946. Maddox, another World War II vet, was accepted by Harvard University, but was denied Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) financial assistance because the agency wanted to “avoid setting a precedent,” according to the bill’s sponsors, who plan to reintroduce the proposal next year.

Consistent with President Biden’s equity emphasis in federal programs, VA recognizes the racial bias and pledges to rectify it.

“We fully understand that there are disparities in discharge status due to racism, which unfairly disadvantage Black Veterans and, sometimes, wrongly leave Black Veterans without access to VA care and benefits,” VA press secretary Terrence Hayes said by email.

View this post on Instagram